Of Blood & The River

Jacob Rakovan

Acknowledgments

Excerpts from this long-form poem have appeared in The Chicago Review

and Drunk in a Midnight Choir

“But when I had besought the tribes of the dead

with vows and prayers,

I took the sheep and cut their throats over the trench,

and the dark blood flowed forth, and lo,

the spirits of the dead that be departed

gathered them from out of Erebus.“

Odyssey Book XI

Sing.

Outside the girdled ring of firelight,

the city's floodwalls,

the shakily chalked circle and

the thousand names of god.

Call the dark up to speak.

Hang the deer from the rusted swingset

Let the throat open.

Let blood be a song.

Be a river.

Let the black song splash against

the galvanized washtub.

Pour blood in the ditch

and sing a litany of names.

Put questions to the woods,

to the mine

to the ridges

to the grave

to the cold stars of our forgotten home.

Let gun and stolen hoard speak.

Let the door of the house hang open.

Let the earth disgorge what it holds

Let the catfish-barbed mouth of hell gape.

Sing.

Warnie Risener, hillbilly conman,

entrusted with keeping of store and post office

has engineered a plan

with Harland Roark.

They have stolen a safe filled with banknotes

the mortgage payments

the back taxes

the book of credit accounts

and the Sears & Roebuck checks.

Warnie has run, been caught, gone to prison.

The safe and money have not been recovered.

Warnie has done his time in silence,

grimly waiting within the walls for the jailhouse key.

Warnie has kept his mouth shut,

tight as a gunsafe lock

knowing how to keep a secret

and the metal doors swing wide.

Harland Roark, an educated man, a schoolteacher

with two daughters

and a criminal inclination

is thankful for this.

Warnie's Colt Police Positive .38 Special

has been used to put a bullet

in the workings of another man

to burst all his intricate plumbing

and let his death come leaking out

in a mine-dark stream

the unsung steaming song

that clots in the washtub

that the ditch-clay drinks.

Warnie has piled the safe

and money in his wagon.

He flees. It is winter

the mud is frozen,

the cows huddle in the cold

the houses are closed

and turned in on themselves

dreaming of spring.

Kentucky is frost and black wire

dead grass and river-ice and blood.

Warnie flees the pooled death of the man

the brittle light of the broken store

the certainty of more jail

a hangman's hempen pearls

and he goads the recalcitrant horse

onto the frozen road of the Ohio river.

(All rose soil

and wormfood below.)

Protest and lamentation of heavy white ice

catfish slow beneath it in cold mud

carved stones in muddy water

compressed snow on top, creaks and cracks

under the axles of the wagon.

Black birds in the bare trees.

The melancholy shore.

The safe, heavy as guilt and God

the hot gun in his hand

fleeing what he had wrought

branded with blood

and bloody doings

across a frozen river

came my family

into the land of my inheritance.

Nolda Roark, Warnie's woman

daughter of his accomplice

dowry of silence

with her bloody bride-price

rides in the wagon

a blanket pulled around her against the cold.

These progenitors bring forth all my line

carrying with them blood from Ireland, and Scotland

from Africa and the hills they flee.

Filled already with an unknowable past.

Marked with money and with murder

secret history of the hollers:

coal tattoo of blood, Abel bleeding in the store-light

midway between one riverbank and the next.

(Like leaves they gather on the shore

and wait for the boatman

the dead in throngs, to speak

with bloodstained mouths and hands

weary seed of Adam

gathered at the river.)

Nolda in her decline is frail

indecipherable, a gaunt white ghost

that haunts my childhood, and beyond her

through a glass, darkly, those dim angels

those giant's bones holding up the sky

Gog and Magog, progenitors and ghosts

river of blood, and music.

Like the hills themselves

there is no answer,

no locked garden gate

no sword of fire

no story of origin or emergence

for the people who chase coal into the earth

who sing songs of murder and the workhouse:

even now sing.

Though the mines and factories shutter

though the water fills with poison

though there in no there, there anymore.

Between one shore and another

death watching like black birds in the trees

Arsenic and chromium, mercury and benzene

the black eyes of river rats, cats in the unlight

Poison water, poison air, and all things burning.

When the Cherokee came to these hills

and valleys where the Scioto lived

the mounds sat ancient and ownerless

throbbing with empty power

a vacant church with kicked-in windows.

They told a story of a people whose skin burned in the day

who went forth to war by moonlight

and lived in the earth, pale as milk

and fearful of the sun.

Blue bottle fly maggots in the rotten soil.

We inheritors of the ancient earth

riddled with strange bones and stranger ruins

these nameless dead.

In Magoffin county

the blue Fugates bear a taint in their blood.

Blue in the skin when cold

the robin's egg I put my thumb through

India ink and a jailhouse needle

cornflower, chicory under a deer stand

the swallowers of silver.

Interbred until the other shines through

the star's blue light a cold blush, a coal tattoo, colloidal.

They are the children of the sky, and await

the road that will open their holler

their twining bloodline

to the larger world.

That the sons of God saw the daughters of men

that they were fair;

and they took them wives of all which they chose.

And the Lord said,

My spirit shall not always strive with man,

for that he also is flesh:

yet his days shall be an hundred and twenty years.

There were giants in the earth in those days;

and also after that, when the sons of God

came in unto the daughters of men,

and they bare children to them,

the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

Even as Nimrod, a mighty hunter before the Lord

and the beginning of his kingdom was Babel

They will find skeletons of ancient men in the mounds

of giants who built the hills

whose bones are the hills

whose skull is the dome of the sky.

They will carve dead giants from soapstone

charge a nickel a peek.

These sideshow gods

these midway wonders

The wild men of the woods

cyclops skulls with mammoth tusks

mothmen and skunk apes

all my kin.

Men plow rocks with runes

from Midwestern fields or scratch them themselves.

Dry seasons bring from the river a stone

carved with an expressionless face, forgotten names

neither Kentucky nor Ohio can claim

this lost kingdom, this broken tower.

Every place, no place, our place.

The history of every family is a history of the world.

In Magoffin county, the Roarks

are counted among the numbers

of Melungeon, the “Portuguese” and “Spanish”

bloodline mixed and uncertain

claim Cherokee grandmothers

forget freedmen and slaves

recount olive skin

remark upon Keloid scarring and curling hair.

Black blood, slave blood

exile-blood of outlaw and outcaste

white trash, Scots-irish balladeers

mine and mountains

secrets the blood keeps.

Nolda Roark Risener

pale as a sheet on a line

white as a frozen river

white as river ice

when she is carried to her grave

her casket opened to the sky

her stitched mouth to sing

and the Old Regular Baptist Choir

(that coven of the Cherokee Princess's grandchildren)

without instrument sings

in liver-spotted hymnody

ten thousand years

shall we gather by the river?

That river

wider than the Mississippi

at Thebes

At Cairo

most-polluted river in the United States.

Infected vein on the heart of the country.

In the Seneca language ohi:yo', good river.

Woe in the language of the angels.

Claimed for France by LaSalle

and his Italian cartographer.

Conduit of the west,

swollen with barges,

swollen with black coal

swollen with Selenium, Benzene, Arsenic

swollen with Tetrachloroethylene,

swollen with Chlorodibromomethane

swollen with Hexachlorocyclopentadiene

swollen with Nitrosodimethylamine

swollen with 4-methylcyclohexane methanol

swollen with death

in all its polysyllabic and proprietary names.

Weariest river that winds to the sea

we have gathered on your banks

to await the judgment.

What do the dead sing?

They sing:

a litany of names.

They sing:

Down beside, where the waters flow

Down on the banks of the Ohio.

They sing:

We are rubber teeth in a vending machine

patched overalls, corncob pipe, felt hat

toothless criminals, illiterate murderers

incestuous cannibals, idiot children.

Sniffers of glue. Huffers of gasoline.

Moonbeam McSwine, Sadie Hawkins

moonshine stills and banjo melody.

We are wild men, our beards tangled with hawthorn

our ragged furs hanging in Morris-dance tatters

our antlered heads scraping the sky.

Digging ginseng on another man's land.

Deer Poachers. Horse Thieves.

Union troublemakers and Scab-Shooters.

Bootleggers and Meth-makers

Dope Farmers and Pill-Sellers

We are the gunshot on the next ridge,

the smoke of a stranger's fire.

We are that thing that squats in the dark

outside the fire's ring,

those who tear asunder,

those who glisten horribly,

the flesh inclothed

the evil questioners

the destroyers

the devourers

those born from the monstrous mother of the world.

Drinkers of strychnine.

Handlers of serpents.

Cannibals and killers

We are the dead, and the end of all things is in us.

There is no end to beginnings.

Nolda Roark crosses the frozen river, forever

expressionless stone without a state

young and not yet deaf

she brings forth

Norma, who will die of childbed fever

begetting Joyce

who begets Neva

bringing all my line into the world

that new shore she cannot see.

How many deaths

do we carry within us, even now?

What mercy of blindness have we been given?

What dim shape below the ice?

What chemical cloud in the river?

What slumbering lump of cancerous growth?

What urge for the bottle, or the needle

or the pills crushed on the dinnerplate?

What secret name does our angel know?

Warnie, with his gun and killer's hands

heads towards a future he imagines is free

imagines himself outside of jailhouse walls

his neck free of the rope

but He and Nolda are trapped in the moment

fish in the ice of time

dead and speaking

their smiles frozen light

silver on paper.

Their voices wax cylinders

scratched film waiting for a spark

to send them creaking

to motion again, these marionettes

Pontius and Judas

smiling and smiling

cheery as wax fruit.

In 1925, on Virginia Beach

after ices, a walk on the boardwalk

after Vernon Dalhart singing on a crackling Victrola.

Warnie and Nolda see the sleeping prophet

The dreamer of Atlantis and Egypt

The Miracle Man, Edgar Cayce

Reader of past lives, faith healer and mystic.

He, oracular, somnabulant, in a stentorian voice

tells Warnie that his heart is bad.

That his blood is slow, is cold ( is black)(is bile)

Warnie is a dead man

made to walk upright and smile.

A limberjack whittled from spare kindling wood

dancing in time

to a song he cannot hear.

whether there be prophecies, they shall fail;

whether there be tongues, they shall cease;

whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away.

Warnie's bad heart will go whoring.

Nolda will shine his shoes

and block his hat

before he goes, each night.

He will not work, citing his bad heart

his slow, cold blood.

He will trust this sleeping doctor

and never ask why.

I'll be carried to the new jail tomorrow

Leavin' my poor darlin' alone

With the cold prison bars all around me

And my head on a pillow of stone.

Saturnine Warnie fathers Bee-Bee Roark

on Nolda's sister Oggie

Nolda delivers Bee Bee

her husband and her sister's child

without complaint

and brings from her own body

Norma.

Norma, pig-pink

squalling for milk

an infant mouse

a blind worm.

Born in the house

bought with takings from the post office job.

The house that stands, today, open

with broken windows

and food on the table

a ruined house of silverfish

and wet-black decay

crumbling paper and rot

mice nesting in the chewed books

the wallpaper mouldering from the walls in ragged strips.

Not even the worst or most haunted

of the houses that I dream in.

This house.

Resting place for the safe

empty iron crypt of history

dragged across the frozen river

housing only paper now

housing the gun

the bloodguilt of a nameless man

and his ghost

birth certificates with floral blue borders.

TheseLares et Penates

these prayerless iron godsof my house

indifferent to petition.

Norma Risener grows

at the foot of the hill

in the house built with stolen money

in Scioto Furnace.

Before the city water comes,

the houses all unplumbed

in her fathers store

Roark Risener Dry Goods and Grocery

on Dogwood Ridge

that knot of flowers

till she is Sixteen

and the road comes through the holler.

In Appalachia, they say the dogwood

was the tree used to crucify Christ

cursed to never again grow large enough

to build a cross, or a gibbet.

.

They say it flowers in Easter

when Christ comes out of the earth.

(That winter sun thawing the hollows,

that groundhog, that black bear)

That the robins are still splashed with blood

from when they lifted the crown

of thornwood, the knots of whose brush

tangle on the ridges like razor-wire.

Everything is holy.

Every ridge is the place of sacrifice.

Every hilltop the place of the skull.

Everywhere is the center of the world.

I have stood atop the hills

and called to the frozen stars

and they have answered

in a still small voice.

The road that comes

is what will be state route 140

a winding track through the hills

a road I have seen witchlights hover over

in thick fog

like a red blood bell on the road

an intelligible sphere

a car for the black sun

like Jack with his lantern

unwelcome in heaven and hell.

A ghost-thick path

that creeps through wheel-less rusting cars

past road side pigpens

past dogwood and thornwood,

past black birds and brambles

and boarded-up gas stations

toward Jackson

north into the flat heart of Ohio.

Woe, woe, woe,

to the inhabitants of the earth

Edward Walker (called Pete) from Wapokoneta

a town which will birth

the first man to set foot on the moon

comes with the Civilian Conservation Corps,

building the road,

all slick brown hair and slicker talk.

In the furnace it is summer

and Norma is in her parent's store,

selling DRY GOODS and COLD ICE CREAM

as the sign says,

selling COLD BEER and HOT COFFEE

in her sixteenth summer.

Edward is thirty, and thirsty with the dry years

when first they meet.

The girl from the Furnace

and the moon-man from Wapokoneta.

(Pale as a bluebottle worm)

Death hangs over the ice cream and the dry goods

the cold beer and hot coffee

death is thick in the kisses of Edward Walker.

Like thornwood and flowers.

Evadna Jean Walker

their first child

lives eight brief days.

Her kidneys failing,

the uric acid and toxins

burning holes through her body

and ever after, among my family

there is nervous checking of diapers

after every birth

the memory of the burned child

eaten from within.

Blame poison water, or bad blood's welling

blame the cracked-snake helix of our ancestry

blame the sulpher fog, the coal-ash water

the sleeping dark of the mine

blame lead pipes and paint

Or the coal scrubbers,

The absentee landlords,

the buyers of mineral rights

the devourers of the under and the black

blame luck, or fortune, or the blindness of the angels

blame the hobbled god

the limping devil

the cold, indifferent sun

or liver-spotted hands of the saints

In a photograph, Edward Walker and Norma

stand in front of the grocery

his face is crueler, older

hardened already by drink and loss

Norma is wrapped in fur

her face frozen in the moment

looking forward towards the doom that comes,

sure as a filmed locomotive.

Sure as winter.

Sure as woe.

At nineteen, in her bed,

burning with fever

Norma's mind dissolves to a single hot coal.

The midwives and witch-women confer

place a blade under her birthing bed.

To cut the pain, to cut the flow of blood

In blood.

Above a knife's edge.

Through the ruin of her mother's body

comes Joyce Ann Walker.

Take boneset for cold.

Take Poke for rheumatism.

Jimsonweed for Asthma (not too much.)

Sassafras for cleaning blood.

Wild Cherry for coughs.

To cure a child of Asthma

measure him with a stick of sourwood

hide it in the chimney

when he outgrows the stick, he outgrows the sickness

To stop the flow of blood, a bloodstopper can

recite Ezekiel 16:6 and pass hands over the wound

but there are no stoppers of blood

of that flood of history for Norma

and death comes like fire in dry brush

like a hole burnt in film,

like the mine falling in,

like the silver bridge falling

like the burning of a meth-lab house

like a cloudbloom of poison in the river

like coal-ash in a creek

comes the blood.

To heal a burn, say:

“There came an angel from the East

bringing fire and frost.

In frost, Out fire.

In the name of the Father,

Son and the Holy Ghost.”

Edward Walker, drunk on Rittenhouse Rye and sorrow

self pity mixed with whiskey and water

blackly drunk on the nothing that he has

this burn that cannot be healed,

this fire,

this frost

that burns the world to cinders.

Lies down on the train tracks

the rain coming down like a cow

pissing on a flat rock.

A train coming.

Sure as winter.

Sure as woe.

The Norfolk and Southern

splits his head open like a melon.

Warnie and Nolda leave the child in the hospital

for the first, endless July of her life.

She is fed, and changed, a screaming orphan

She is nursed by cold ghosts

in a loud, white sound.

In 1934

John Dillinger meets with three bullets

his father says

That's not my boy

That August, comes Lil Abner

the outhouse-crescent-cutter

come Dogpatch,

come Daisy Mae Scraggs

come Pansy Hunks

come Lucifer Ornamental Yokum

come Nightmare Alice

come Moonbeam McSwine

come Jubilation T. Cornpone

all my kin.

Nolda and Warnie hang a picture in The House

(where the gun sleeps in its metal crypt)

of Norma

pretty in her casket

among the lilies

They hang one more picture beside it.

High on nails

Joyce, fat in Sunday clothes,

perched awkwardly on her mother's grave.

They take Joyce, adopt her for her inheritance

her father's head

a pinata full of money

a bone-safe

A conjer-ball

buy Risener's Cafe, on Front street

in Portsmouth, Ohio.

(A bar for the riverfront

for the poor who roll downhill

till they come to the water's edge

for the rats that come up from the river

their eyes shining

their coats glossy

and sleek as beaver

big as rabbits)

Here is whiskey

and the soft song of it.

The shine of threadbare bar stools

of afternoon light

through hand-smeared windows.

Here are men

too rudely shaped for war

and laughing women

with powder-red cheeks

and stockings with black seams.

Here is beer, cold in a brown bottle

and river-ice hoarded in straw

and Texas swing on the wireless.

A world built against the day outside

the dead on the French hills

in the mountains of Italy

in northern Africa, and the Pacific

over the hills and far away.

Here is the lie of safety, and the brown bottles

and the men fighting in the gravel at night

and the women drunk, and the dead

outside the window looking in

the music, the left-behind

the lame and the nearsighted

dancing in a whirl of light.

Warnie calls Joyce “Pee Wee”,

in mockery of her thick and ungainly body

One hundred and fifty pounds in first grade

takes her with him

to whorehouses and honky tonks

to brown bottles and river ice

a drinking buddy, a son, a lover.

Warnie teaches Pee wee

How to hold and point the family gun, that devil's fiddle

How to charm a whore, how to cheat at cards

How to cuss and fight like a boy

How to keep a secret.

Norma still blocks his hat

and shines his shoes

when the bad heart

and slow blood rises in him.

Now that bad heart has a companion

and instead of her sister

it is her grandchild

born in her daughter's death

that takes her husband away in the night.

Off to the whores of the hotel Hurth

to whiskey and black water.

Does her dead girl keep her company

in her long and lonely vigils?

Does she burn, still, on the knife edge

between one world and another?

In another home, a birth remains nameless for three years

another hungry mouth in an overburdened house

in a crush of brothers and sisters

child of Beatrice and Howard Russell

Brother of Garland

of Buford

of Winford

of Jim

of Joe

and of Falkie Deem (called Deemie).

He calls himself “Mirror”

the only word he has for self

and this will, in time

through the alchemy of speech

and the familial shape of names

become Milford.

Pee Wee paints houses

buys herself a second-hand 1949 Triumph Thunderbird

She fights with men

drinks whiskey

rides her motorcycle into the lake

while standing on her head.

She is barroom bravado and swagger:

She wears a studded leather belt

that spells out “Joyce”

handsome, if never pretty.

She sells ice cream and dry goods

cold beer and hot coffee,

frys hamburgers in a corner of

Roark & Risener Dry Goods and grocery.

Milford is too poor for Brylcreem

melts Morrell brand Snow Cap Lard on the stove,

to style himself a perfect duck's ass haircut.

On cold days the fat recongeals

white and opaque as candle wax.

Pee-Wee tells Clorene, her best friend

that this is the man she will marry.

Milford is pretty and useless

but he struts, a bantam cock

into the smell of sizzling meat

ICE CREAM and COFFEE.

Joyce wants him

the way poor girls want tinsel

want something shiny, cheap

a carnival mirror

shoplifted drug store lipstick.

The way a catfish follows the oil

through the lightless river

the smell of congealed blood-bait

of breadballs and WD40.

Moonbeam Mcswine & Sadie Hawkins

Warnie's bad heart offers Pee-Wee a car

if she will not marry Milford

If she will remain his only

bride of the slow blood

but she is adamant

and they elope

with only the Triumph.

Milford rides on the back

an ornament, a mirror for Joyce

his larded hair glistening in the heat.

Bloodbait

They have only daughters.

Each dutifully checked

for the poison that eats from within.

Each with it's own bad heart growing in her center

like a thornwood tree

like a coiled copperhead

each a lure for something hungry in the dark.

I was so hungry my belly thought my throat was cut

Pee Wee takes pills to keep her weight down

Amphetamine and Dextro-amphetamine,

called Biphetamine

called Black Beauty

called Black Bombers

called Black Birds

though her pregnancies.

The black capsules, those magic beans

transform in amphetamine psychosis

to clowders of invisible cats

and Joyce, in fitful night terrors

calls out, over and over again

Put the cat out. Put the cat out.

When there is not, has never been a cat.

A story told in Kentucky tells how Jack

who had never been afraid

(that killer of giants, that climber of beanstalks

that headstand-trick rider, that handsome boy)

left in search of work, and came to a town

with a haunted mill.

If a man could stay three nights

and live, the curse would be lifted

the miller and his wife would fill a flour-sack

with gold.

On the first night, the dead boys came

and bowled with skulls

and Jack whittled them down

so they would roll

gambled and drank whiskey with the dead boys.

Blue as a coal tattoo, cold as river-ice

On the second night, the drowned girls came up from the pond

trailing minnows and rotting catfish, with weeds in their hair

and bluebottle flies and Jack fiddled all night,

and the dead girls danced, white as dogwood flowers

till the sun rose.

On the third, while Jack cooked his dinner

came the cats, all long and rangy,

black as a tar road.

put the cat out

Gathered round, hissing, said sop doll

tried to dip their paws in his soup-beans

till Jack took his buck knife

and cut off one of the cat's paws

and threw it in the corner.

In the morning, the miller come round

and said his wife was feeling poorly

and Jack pulled the blanket off her

and her hand was gone, the bed soaked in gore.

These bloody beds. Where stories start and stop.

Pee-Wee's cats climb on the ridge of the roof

on the headboard. They are eyes in the dark

come to steal the babies' breath.

They are the pills, endless succession,

gleaming black, preventing sleep

the lead-gas addled rumble of the Triumph

scream of the Thunderbird

dream-trance voice of the Sleeping Prophet.

When the first girl comes

she comes in blood

above a knife's edge

(to cut the pain)

the blood soaks through

the mattress, and falls on the blade

the bed as bloody as the miller's wife

as her mother's ruin.

The girl is named Norma Jean, after her

still wrapped in lilies on the wall

black and white as a tree in winter.

Unknowable mother

her dead eyes under glass.

That giant, that god

that soapstone wonder

that stone face in a river.

Then comes Neva Dean, my mother

the four still ride only the Triumph

the groceries hanging in the saddlebags

the babies between them,

sticky with sweets

the bike heavy and slow

on the road her father built

through the thornwood,

the cross-trees thick with ghosts.

Joyce will say of Milford

I had to teach him how to spell his name

but at least he was a handsome man

He will work in the store

propping bare feet up on the counter

trimming his nails with the bologna knife

Snuffy Smith and Lil' Abner

Dogpatch and Graceland

He fathers two more children on Joyce

Nina Lene and Naomi Lynne.

Those black cats

clustered around the birthing bed.

Their bodies black and starless

Their eyes wide as dinner-plates

The bad hearts spinning in their chests

like dynamos in the dam.

Milford feeds milk to his blue-tick hounds

(bought on credit in the grocery)

and lets his children go hungry.

When Joyce runs off with another man for a week

bowling with skulls, dancing with drowned girls

he does not feed his daughters for five days.

Naomi hugs a litter of hound pups to death

so lonesome for something soft.

The house is untended and shuttered.

Warnie keeps cows in the barn

and the ghosts of the dead man, of Norma

come from the safe

the bed

press their dogwood-blossom faces

against the windows.

Maggot white.

Neva is left at the house at the morning milking

and picked up at evening milking

she goes to school in the furnace,

Hananiah, Misha'el, Azaria

(Her hands beaten bloody with a yardstick,

a stick of sourwood she never outgrows)

though she lives above the bar,

in town.

Each day she sits, her back to the window

so as not to see the dead man's face

she stands with the cows for warmth

in the steaming barn

and her grandmother's ghost stands with her.

The grave is cold.

Joyce and Milford leave the girls

in the care of Milford's sister Eveline, thirteen.

Norma cuts herself digging in the creek

and runs to the neighbor

with blood pooled in her hands.

Neva severs Nina's finger with a shovel

digging holes.

They feed the furnace till it glows

red as a poker, and are stayed

from throwing water on it

and blowing the house apart

by Milford's brother Joe

who has dreamed of them, alone.

Whether there be prophecies, they shall fail

Joe comes in time to grab Eveline's arm

Joe waits with the girls

until Milford returns

and beats him through the house,

breaking tables.

for he has rescued us from Hades

and saved us from the hand of death,

and delivered us

from the midst of the burning fiery furnace;

from the midst of the fire

he has delivered us.

Joyce tires of Milford's empty handsomeness

carnival mirror image of a man,

dusty tinsel and greasy cherry lipstick.

She leaves

and abandons the girls with Nolda

already ancient

they call her Granny

the witch in the woods in the candy house

Nightmare Alice and Scary Lou

the not-mother, not mother to their own.

She teaches them:

I don't hate you, honey

I just hate your ways

teaches them:

if you want to be purty

wash yore face with a baby diaper

(ammonia in linen)

teaches them:

Shall we gather by the river?

Joyce claims Warnie's gun

waking it from the iron box,

and dreams of murder

and shoots her first man, Duffy Rollins

outside the 440 Bar on Market and Second

Duffy survives.

A carnival trick-rider

with a bullet in his teeth.

The girls cluster together, motherless

a whispering conclave of cats.

They crawl through the hole in the wall

into the bar after closing

steal popsicles and treats,

and eat until they are sick.

Gather shoes into bed at night

to throw at the rats.

Grow wild and untended.

Sleep four in a bed, crosswise.

Catch chiggers in tall grass

and are slathered in salt and Crisco.

Like she was going to fry us.

Neva says.

One night, Joyce appears at the window

with Duffy Rollins

the sideshow wonder

the man was pierced and did not die

and the girls gather in their nightgowns.

She is at the helm of a truck

filled with a hoard

stolen from a school.

She throws them a globe,

a gift of the world,

and vanishes into the dark.

Warnie's bad heart rises

a cancer of the groin

a whore's blossoms

a killer's killer.

A catfish big as a Volkswagen

breaks through the frozen river

of the slow, cold blood

and swallows him down to hell.

Bloodbait and oil

The door in the fishes mouth.

The fountain of cats.

Barbed mouth of the dark hollow.

black water

Joyce is arrested for whoring at the Hotel Hurth.

Nolda hides the morning paper from the girls.

The neighbors shove the paper through the mail slot

letters that need no addresses.

There is Joyce, famous and unknowable

A newspaper cipher, a bubblegum riddle.

A dream in the night with the world in her hand.

Filled with criminal glamour and bad ideas.

Milford remarries, a woman with daughters

brags to his brother Joe about hishouseful of whores

and how he is availing himself of them.

Joe beats him senseless, again.

A cure that will not take.

There is no stopping the flow of bad blood,

no exorcism by ass-whipping.

And Joe is off to Vietnam.

I meet Milford once, we go gathering hay bales

in a battered blue Chevy pick-up.

He offers me a Hamm's beer from a six-pack ring.

He offers me a plug of Red Man chewing tobacco from his pouch

At the age of six, my arms trembling

I strain to lift the hay bale into the truck,

see the dry and dead fields from a rainless summer.

Listen to Hank Williams on the radio.

In the great book of John

We're warned of the day

when we'll be laid

beneath the cold clay.

We fish once and only once,

for bluegills in a shallow creek.

The minnows hooked through their eyes for bait

lure no channel-cats or hellmouth.

He shows me a raccoon in a cage,

savage and miserable

more prisoner than pet.

When he is dying,

I go with his daughters

to gather his cattle for slaughter,

to pay his hospital bills.

The sisters stand, frightened in the mud

and in the end, I drive the cows up the plank alone.

His new children do not thank me

At his funeral,

his flawless steel grey duck's ass haircut

a sharp black suit, and lilies.

Photographic flash in the viewing room.

Lights him like a crooner,

like a criminal, famous

The Hillbilly Cat.

Dead houses on his land

fill with dent corn and rats,

with broken windows.

His cows hang from hooks,

their black blood draining.

Weep no more, my lady

Oh, weep no more, today

He leaves me this:

For 'shine, take sweet hog feed and white loaf sugar

and Red Star bread yeast, let it brew. Don't drink the low wine

or the doubles, and throw away the heads and tails.

A cinnamon stick and some apple juice

will make it so's a lady can drink it.

Even this a lie, words I place in his mouth.

A scrawl of ink from some distant relative

the family recipes

Beans and cornbread

with a ham hock

sausage gravy

red-eye gravy

drop biscuits

7-up cake

Pineapple upside-down cake

Jelly from Possum grapes,

Dandelion wine

and sugar-washed shine.

All learned second or third-hand

as an alien, an outsider, an onlooker.

Too late to Christmas,

we eat cold leftovers

from the foil pans.

I have learned my hymns and union-songs

from the borrowed hiss of vinyl

My banjo-roll from a yard-sale book.

Hank Williams and The Louvin Brothers

Loretta Lynn and Woody Guthrie

Webb Pierce and Jimmie Rodgers the yodeling brakeman

Jean Ritchie and Maybelle Carter and The Hillbilly Cat

Merle Travis and Hazel Dickens

Florence Reese, forever asking

Which side are you on?

all my kin.

Joyce marries Arthur “Bud” Kitchen

who she plucks

from a bar on Second Street.

A man with more courage than sense.

He takes a mistress named Anna May

and JoyceBusts all the winderlights out of the house.

Bink, (husband of Falkie Deem) is bartending

and Anna May sits at the bar.

Joyce comes in, a black hat

a fighting man at high noon

saysI'm a goin to go home and fetch my gun

returns with the fiddle in hand

and plays a tune for dancing

shooting the woman through the vagina, and bar stool.

The bloodstain remains on the ceiling

my family's mark in Portsmouth, Ohio.

Anna May is rushed to a hospital

and loses so much blood, they suction it

from the operating table, and shoot it back in

like the Miller's wife

like Norma, before the lilies

She bleeds and bleeds.

And when I passed by thee,

and saw thee wallowing in thy blood,

I said unto thee: In thy blood, live; yea,

I said unto thee: In thy blood, live;

The doctor has to change in the yard

when he comes home

looking like a slaughterhouse

like an abattoir

in butcher's red and white.

Anna May lives, to piss herself

for the rest of her life.

Joyce goes to Marysville

to the Ohio Reformatory for Women

Because she aimed for the offending part

and not for the heart or head of Anna May.

She spends a brief soujourn there

learns to knit

learns to measure her time in cigarettes

learns to try to love Jesus.

When she comes from prison

she towers in her heels and yellow pants.

A Kool dangling from the painted wound of her mouth.

The neighbors say “A Giant is here for you”.

They are always Giants,

who build the roads, the hills

Who rend the world apart

whose borrowed bones

shield us from the stars' destroying light

from whom Jack steals

the golden eggs of the sun, and fire.

Joyce the Giant, who vanishes, is shot

on December 15, 1967

the day the Silver Bridge collapses.

46 people fall to their deaths in the black water.

A man with membranous wings is seen in the wood

and the world comes apart

but the giant does not die.

Pee Wee, the Giant, the devourer, the undying

everything but mother

(her heart a hospital, a loud white sound

the roar of a gun, a ruined house)

takes the girls

takes the safe

takes Warnie's gun

that killed a man in Kentucky

that shot Duffy Rollins

That shot Anna May

Take's Warnie's ghosts in her mouth

to Hobart Eugene Mcginnis

called Red.

Red as a house-fire, as a coal grate

as a playing-card devil.

Hot as a two-peckered billygoat.

Hot as a fresh-fucked fox in a forest fire.

She will die married to this man,

an illiterate, a dealer in second-hand cars.

A trucker, with a short temper and a heavy hand.

I will first taste whiskey in his house, at six.

From a plastic dispenser marked

break glass in case of emergency

Red, in his folly, will take a mistress.

Pee-Wee hears them on the phone,

her bad heart rising

Is Joyce-Ann still your little poodle dog? asks the woman

and Red laughs, and assents.

break glass in case of emergency

The fiddle comes out, and plays its only tune.

Red is shot in the mouth.

He flops on the linoleum,

Joyce Anne lights a Kool 100

and sits at the kitchen table

flipping ashes in a tiny cast-iron pan.

Red pounds himself against the floor

a catfish in the bottom of an aluminum boat

hooked through the lip

the dial-tone coming through the phone.

Joyce calls her daughter Naomi,

says "Come over, I've kilt Red "

but when Naomi comes

Red is floundering on the ground

and once the blood is cleaned from the floor

and the gun hidden well away in the safe

It is eventually clear that he will not die.

An ambulance is called.

He can write nothing but his name.

Cannot speak, his mouth swaddled in bandages.

he was a-cleaning his gun says Joyce

says Pee Wee,

says Warnie's ghost in Pee-Wee's mouth

say the black cats in harmony

say the dead boys blue and cold

and Red is stitched together, a quilt.

The doctors will say

That Red was doomed to die,

a clot in his brain had given him violent headaches

made him short tempered, volatile.

Say he was cured by the bullet.

That bled out the devil, the clot, the bad humour

the black birds that roosted in his head.

Red's heart monitors go wild

every time Joyce comes into the room,

his mouth bandaged shut

his letterless hands mute

The doctors think him excited.

Glad to see his loving wife.

He returns home, and Joyce and Red fill

their childless house with dolls.

Apple-heads and Mammies

Porcelain and velvet

and rag doll daughters

who never cry.

Go to a double-wide church

with a paint on velvet Jesus

with plaster praying hands.

Naomi takes the gun

and fires it at her husband, wildly

when he is caught with another woman

breaks her arm in the struggle.

she takes the safe, and The House

grows weed in the roofless smokehouse.

Their daughter is run over by a car

and stitched together, a quilt

her bones all broken

held together by a shining cage

and she the frantic raccoon within.

In her adulthood she will favor speedballs

will make crystal meth in her garage

will arrive at the funeral of my sister's child, babbling nonsense

her husband nodding out in the bathroom

the whiskey priest kicks the door in.

She calls me, when her child is pregnant

to ask how to procure an abortifacient

to slip in the child's drink unaware.

I do not help

do not say Pennyroyal.

Yarrow, Saffron, Rue, Tansy

I spit them out, slow

all the bird-bones of your secrets

that time has made smooth as stone

minnows hooked through the eyes.

Joyce and Red run McGinnis Trucking

a fleet of Mack Trucks, a used car lot

keep a billy goat tied to a tree stump

porcelain turtles with pink human genitals

keep books with leather covers

INCREASE YOUR PSYCHIC POWER!

UNIVERSAL MAGNETISM

THE SLEEPING PROPHET

in a dusty attic

and grow old.

Neva Dean Russell has grown,

from the wild and feral child greased for her chiggers

from the girl with the ghosts at her back

from the child with her knuckles beaten bloody

because she could not let the others answer

to a homely valedictorian and has gone off to college.

In Athens Ohio, a town nestled in the hills.

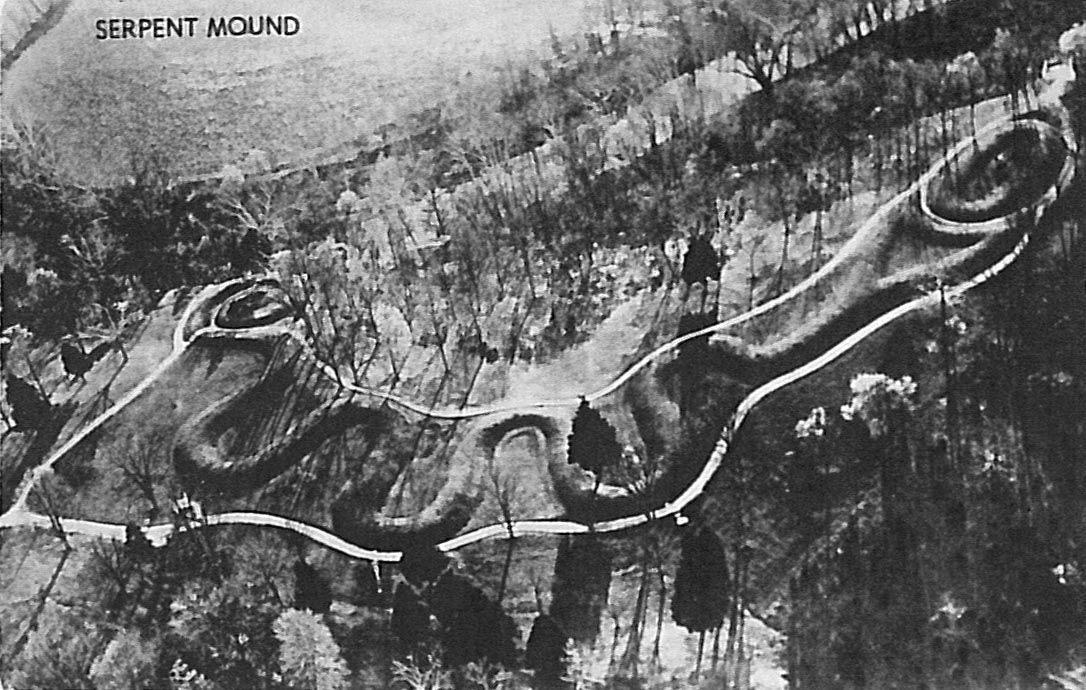

Atop the bones of the Adena and the Hopewell

the giants, the builders of mounds,

the carvers of obsidian hands

home to Ohio University

the Athens Lunatic Asylum

demon-haunted Simm's Cemetery and it's hangman tree.

The brakeman ghost of Moonville tunnel.

She meets my father, a man so ugly

that he must bring a pizza when he comes to see her

so no one will know she is sleeping with him.

They have a shotgun wedding

beneath the implacable stare of plaster saints.

The troll in Bakelite glasses, the homely bride

pose smiling in a green field

in front of a willow, far from the river

the sisters all bridesmaids

Red and Joyce not in attendance

Bill and Naomi, high, in checked polyester.

Down in the willow garden

where me and my lover did meet

She does not know when he was a boy he wired his radio

to pick up 1170 AM WWVA, Wheeling West Virginia

those thin hillbilly voices crackling

a promise of some other life

something not built of Polka and Slovak

muttered under the breath.

She does not know the willow tree

is a transplant from the south

carefully sprouted in a Coke bottle

and grown along with the boy

a sourwood stick in a northern chimney.

She does not know he wants to inhabit

the snakeskin she hopes to leave

dry and empty

hanging in the dogwood trees,

they haunt each other

each a mask the other hopes to wear.

And in Portsmouth Ohio

(that dying city atop the mounds

that graveyard of shoe factories and steel mills

that cursed and holy place) in 1975

I enter the story.

Neva and Allen leave school with no degrees

and Al takes a job in the Jones and Laughlin Steel Mill

in Indiana. He builds bridges and cranes,

then works in the coke plant

keeps ancient machinery running.

He is coated always in red dust and grease,

in rust, and oil, and coke

wears heavy steel boots,

his clothes covered in pinhole burns.

We go to live in a rented farmhouse,

on a pig and cattle farm

my first memories are here.

The cattle towering over me

grazing amidst cars on blocks

dead tractors and a useless crane

the cars rotting on their axles

pink mice in the upholstery and

glove compartments

the engines parted out.

The mirrors glinting in the tall grass.

The smell of sun-cracked vinyl.

Brown-eyed susans coarse and nodding

chicory between the corn

poison ivy coiling through collapsing outbuildings.

The smell of pigshit.

The squealing pink pigs

getting loose from the pen

looking through the windows in winter.

A swarm of black ants with their babies

in their teeth.

And Sara Ann, called Jane is born

From ruin to ruin we move.

We buy a house

on Rural Route Three, box 1368

with tarpaper patched roof and settling floor,

with a black rotary phone wired into the wall

a dirt floored extension

we fill with engines

and truck tires,

with chickens and mouldering paper.

My father ties the chickens to the fence

when he cuts off their heads

We pluck the feathers in bright handfulls,

soft down from the belly,

stiff quills from the wings

Pull the tendon in the severed feet

till they close, terrorize the neighbor kids

raise a terrible, one-legged goose,

a dog that bites

fill the yard with cars,

two convertibles with rotting ragtops

two International Travel-Alls

two International Scouts,

one a mail truck with wrong-handed steering

a primer-red 1938 International harvester truck

with a winch and snowplow

A 4-door Chrysler sedan, 3 motorcycles,

and half a Volkswagen

and the zoning man comes around,

gingerly stepping through the tall grass

in his penny-loafers.

And Elizabeth Mary comes, and after her Rachel Danielle,

by another man but bearing our name.

And this seems far from the hills,

though our neighbors are from West Virginia

hunt squirrels on our acre in the summertime,

though their house is more shack than ours

and it is here I hear the word Hillbilly for the first time.

Always in reference to the former owners, the Heighleys

who roofed with carpet tacks

and put carpet tacks in the rug.

Who let the beams rot

and the floor sag

whose fault it was the ceilings burst

and the insulation hung in tatters

that the raccoons fucked in the attics

that the mice ran

along the tops of the cabinets.

Those mythical architects of our squalor

the hillbillies

who lived there before us.

Because we are not hillbillies.

Though the yard fills

with rusting cars,

with wringer-washers filled with gasoline

and air conditioners

with hives of yellow jacket wasps

garter-snakes and toads in the tall grass.

My youngest sister Rachel

drinks Coca-cola as an infant,

knocks over the bottles

to suck the sweetness from the filthy carpet

her teeth rot black before she is four

and are capped in gleaming silver.

Q. What separates a hillbilly from an asshole?

A. The Ohio River.

Though the house fills with mice, with televisions

with radios and disassembled engines

with boxes of tubes, an oscilloscope.

The raccoons grow tame enough to feed by hand.

Though my dog, off his rope, eats the baby ducks.

Though the rabbits freeze in the winter.

The chickens stand outside the warped door

then bleed out lashed to the rusted iron fence.

Though the carpet grows bare and bald

and the wood shines through.

Though the apples and pears

rot on the ground

and the wasps crawl over them.

Though the record player warbles with Loretta Lynn

and Red Sovine,

the recorded language of a far off country.

Though the sink crawls with blue bottle-fly maggots.

Though my father's incest and ramshackle house

makes us the punchline of every hillbilly joke.

We are not hillbillies.

Q. How do you circumcise a hillbilly?

A. Kick his daughter in the jaw

We are northern, and Catholic, and Slovak

and the Heighleys, like the Adena,

or the Scioto who had gone before

are the Hillbillies,

and the Gurneys, who burn crosses

and stew squirrels, fry their brains in scrambled eggs

who fish for catfish in a hand-dug pond

eat possum and raccoon and woodchuck

are Hillbillies

and the Dugards, the coon-asses

who have almost as many junk cars as us are hillbillies

but we are far from the hills, and are not.

Q. Why can't you convict a hillbilly of a crime?

A. They all have the same DNA, and no dental records.

We have broken the ties of history

the black birds and bad hearts

have no power over us,

the gun is in its safe in The House.

When the tree falls on the house, it is just bad fortune

we live with the roof split open

the ceiling sagging down to touch the floor

eyes shining in the dark

scratch and scramble in the walls.

Oil-rich smell of blood and terror

my fathers hands

his confessionless mouth

blessed by a good Italian priest.

Only say the word and I shall be healed

The dead mouse stuck in the vacuum tube

and it's tail slid under the door

I sit with my back to keep him out.

The dead thing flicking against my back.

Again and again.

My father's high pitched laugh.

We are free, whatever free can mean

in that ruin, that wild place

with the numbers scratched on the mailboxes with a pocket knife

that road's loose suggestions of gravel

that led nowhere but back

to the haunted house, the chapel perilous.

In the room of ruin,

a picture of Warnie and Nolda, framed in gold

those terrifying ancestors, looking over the rotting couch,

the cobwebbed glass lamp

the roof open to the rain, and the stars.

I dream it still, the aquariums filled with dead leaves

and Warnie' implacable, proprietary stare.

That room where I hid with the bleeding whelp

behind my knee from my father's belt.

That room where the dead bowled with skulls

and the drowned girls danced

where the black cats held their congregation

till the fire took it all.

Q. What do a hillbilly divorce and a tornado have in common?

A. Someone's losing a trailer

When Neva leaves, with Rachel and her father

the boy across the street, sixteen and useless

and bound for the Marines

We believe the ruin is all we have inherited.

While she marries on a beach, her silver-toothed

babe in arms, we, left with a photograph

a shipwreck of a house

the eyes of the mice gleaming in the dark.

When the boy is in the Philippines

she returns, and takes up whoring

at the Al-Khazar Topless Bar.

There is no mention of bad hearts

or newspapers stuffed through mail slots

or the Hotel Hurth.

When she feeds her daughters to her husbands

like minnows hooked through the eyes, bloodbait

like cattle forced up the plank and onto the truck

when she teaches them how to charm a whore

to cheat at cards, to keep a secret

there is nothing but silence.

And God is mute and deaf as a principal.

Mother, how you passed them through the fire

under cover of flute and drum

so much coal shoveled into the Moloch

of his bed, the stink of steel mill and unwashed flesh

stained yellow in the sheets

How you left us in the ruin

Your favorite perched on your arm

a pet with silver teeth

the rain coming through the roof

into chipped yellow enamelled pots

mushrooms growing from the carpets

This chosen child calls the police

in her twenties

because of the secret messages her boyfriend

has painted in the shadows of the wall

because of the hidden microphones

that record her thoughts

the secret language of dogs

the spinning eyes of cats in the dark

meth and biphetamine and ether and cocaine

they commit her to hospital for cocaine-induced psychosis.

Now she eats her own young

your special child, runs to her own final beach

her children so many packed bags

left on the dock, a learned art

she thinks she will take one

will preserve one chosen pet, and leave the other

her mother's monster in every respect.

Asks me to write a love poem

to commemorate the act.

To sing to cover the screams

as they are passed through the fire

When my stepfather teaches me how to steal

how to lie, the easy patter of con-charm.

Always flirt, even if you don't mean it

it keeps your hand in

There is no invocation of the blood,

no mention of the ghosts that clot the air

thick as milk, as smoke from a burning house.

I will not tell the lie of my sister's love

How to charm a whore.

When he gives me my first knife

I like the fit of it in my hand

know it for an artist's tool

I will not carve a monument to this repeated crime

How to cheat at cards.

How I glory that knife, alone in the dark

a silver tongue of prayer, a Hosannah

It is 1984, and I stand over my sleeping parents

think to avenge the blows my mother demanded

think to hang all our failings on that goat and offer him up

and slake that ancient thirsty thing

that hangs over me while I sleep, and whispers

think to choose one face for the devil, to kill the giant.

(To cut the pain, to cut the flow of blood.)

Every knife is the threshold of a door

a bright bridge between one world and the next

How to keep a secret.

When he borrows back the knife

and loses it to security in a Tijuana dance-hall

I feat I have lost my ticket

for the gopher-snake, the copperhead of highway

back to the ruins we had left, the bag I keep packed

after he splits my mothers lip with his keys

after the screaming and the tears, the stitches

the broken windows and the broken tables

the Military police throwing him in the shower

the less than honorable discharge.

In my twenties I hitchhike the road west from Ohio

with a straight razor in my back pocket

a bag on my back

a cook-pot hobo-jangling with every step

retracing my steps.

Flat land and endless crucifixion of telephone wires

Wheeling crows and red-tail hawks

flat ribbon of highway

though the hills and mines.

The mill towns and river bottoms

are there, though the faces carved on the stones

in the river are ours

we cannot return.

We are a homeless people

and nothing has been promised us.

In High school, after the fire

takes the house the Heighleys built

takes Warnie and Nolda's portrait down to hell.

After the cars are hauled away

the pond filled with scrap

the frogs shout atop the old washers

the pears lay rotten on the ground

the wasps sing over them.

Old Mister Gurney is dead from heart failure

and his grapes wither on the iron fence.

After the Ocean at night

and the death I do not find there

after a time in Athens

that haunted house

the perilous chapel

where I did not ask the right question:

I come again to the cursed city, the doleful city.

Portsmouth, Ohio

you doomed clot of river mud

inverted bowl of foundry smoke.

You habitation of vultures.

You ruin.

You unholy cauldron.

You stolen junkie's dream.

You crumbling stone on a chain.

O Babel, O Carthage, O Babylon, O Dis

of electric light and color television

of empty houses silent

and the poison ghosts of cold factories.

You pill-mill. You meth lab.

You whiskey-bottle basement.

Portsmouth, you devourer of your children.

You Leviathan of drug stores and doctors.

Behemoth of bad ideas.

Frankenstein tavern

of Cocaine, Methamphetamine

Dilaudid, Oxycodone, Oxycontin

Morphine dermal packs.

City of toilet tank lids

and dinner plates

of metal tubes and rolled dollars

Keystone and Old Milwaukee.

You shipworm-rotten plank I am carved from.

You funeral barge of black coal.

You cold smokestack.

I came to you innocent of blood and wonder

sure that Chicago and the libraries and schools of Athens

had prepared me to be a criminal, a conman

a sideshow talker

a bally man

a snake oil vender

a faith healer

a tongue like a knife.

“Do you smoke?” they asked me.

I proffered a crumpled pack of Camels

but soon I had learned

my apothecary's abecedarium:

Shake-weed and leaf

Gnarled and grotesque buds

Menagerie of fantastic roots,

Closet-grown fungus

Vials of acid, dripped on candy

Terrible powders

offered in a smear

of blue dust on a dinner plate.

Pills purloined from a mother's purse

Sleeplessness from the diet doctors

from Columbia and Mexico

cut with infant laxative and ether.

Flowers for pain,

and for sleep.

All rounded with bottles

of whiskey, and beer.

Prescriptions for pain

a little poison for a pleasant sleep.

From that shipwreck I emerged

by luck by chance and the turn of fortune

Unpaid borrowed dollars in my pocket.

but I say them here that they remain deathless.

All the lost adventurers my peers

My mouthful of moths

clattering against the light.

Eric Deer and Tim Cantrell

Chuck Broughton and Tom King

Anson Edwards and Jay Ferguson

and Danny Bailey and Matt Stepp

that parade gone down to dust.

Ingrid, innocent and brighter

than all the other shades

nail through my tongue

brighter than fire to burn away the cancerous dust

the tired bricks, the sprung bridges

radio towers blinking their dull red light

over the bowl of the hills

like sentry towers in a prison

like blinded cyclops.

You alight like the sun on the hilltops

burn away the polluted river

stand, in your beam of perfect light, deathless

outside of history, you littlest of giants

and Angela, who died singing, and all the rest.

All, all, all my kin

Portsmouth you were never a city for children

who starved within your walls

the muddy water filled with corpses.

O mother holding her baby above the flood.

Poverty-house, burning ground where I was branded.

You Mountain Dew mouth.

You cancer.

You mournful saurian whine of train brake.

You yellow fog of coke plant.

You empty mill.

O my city, o ruin, o hilltop conflagration

where I called the seventy two devils

and found they all have one face

the rotten face of my father

of Warnie and his bad blood

generation upon generation.

O circle against the flood.

O Cyclopean ruin, O Pandemonium

piled by giants high in the mud

beside the poison river.

It is on your muddy bank I falter, Ohio.

Phlegethon, where the damned in torments fry

It is there, on the bottoms

amidst the bottles, the boiling blood

the moon-grin of desiccated catfish

the trash and groundhogs

the rope and detergent bottles

the wood of suicides

I am undone.

A dreamless body in the brown water.

A diver near the dam, a bridge-jumper.

A drunken swimmer against a swollen current.

A blind fish, a three legged frog.

A tumor-ridden rabbit the dogs won't eat.

I write this history for my children

who live far from the tint of your mud

and mourn their cousin forever tangled in it

among those roots

in the dark water.

For the drinkers of poison.

For the uplifters of serpents.

For teetotals and drunks.

For the distillers of shine, and crystal.

For the pill mills and the mound dwellers.

For the Union men, and the scabs shot on the train.

For the drowned, for the fishers of drowned men.

For the miners, the coal barge captains

the train-hoppers, the trestle-swimmers

the butchers, the bridge-jumpers, the blue Fugates

the property-lawyers, the king of the cowboys.

For the moon-men and ice cream women.

For the dead, and for the living.

For my sister, who wakes each day

with an empty cradle.

Who lives

in spite

of all of this, who lives.

Who leaves the dust on the plate

the bottle still sealed in bond

leaves the namelessness of sleep

each day, again and lives.

For my other sisters, who live as they must

in the fog of pills, the rattle of their own voices.

For myself, and my children.

What gods for us?

Carved expressionless faces on stones in the river?

Iron gods of gun and safe?

Petro-plastic Christ of my Slovak grandmother

with broken hands? Merciless gods?

Terrible gods, who regardeth not persons?

River-gods, green-toothed and insatiable?

Devourers of children, catfish-headed

mine-dark, house-fire-bright gods

of kicked-in windows and shouted prayer?

Gods of lightning and mud

and burst levies, the cleansing torrent

swollen with chicken coops and bleach bottles

with bodies and lumber?

Gods of the carried-along?

Gods of detritus, gods of flotsam?

What can I give of joy, and wonder, what music

against your inexorable flow, Ohio?

That is death, and death and death.

These sepia ancestors in their burned portrait.

These ruined houses, these bloody beds.

What stories are mine to tell?

What secrets must I keep?

What have we shored against the flood?

A banjo roll and shape note harmony

lined out hymnody from a broken throat.

We went once, to The House, armed with

candles and the Lesser Key of Solomon

with broken crystals and holy water

to trap old wily Warnie's ghost

that grinning blue devil

who swims in my blood like a fish.

We rattled our empty threats,

Ialdo saboath, Elohim, El, El Shadai

Abdya Hallya Hellizah Bellator, Bellony Soluzen

barbarous tongues of invocation.

Cocksure in jean jackets

and heavy metal tee shirts.

Shook God like a boogyman at the dead.

Shoplifted dinner tapers,

coil of incense smoke.

Hellhotter than a fresh-fucked fox in a forest fire

Sweating like a whore in church

in the fly-swarm of that endless summer.

We jumped in stone quarries, and swam in the river.

Climbed radio towers to howl

at thrones, orders, powers, dominions.

Spray-painted pentacles on concrete platforms.

Drank beer on stone ridges of the hills.

When the man who got our booze

sold his washing machine for beer money

and ripped the porch off his house

and slashed his wrists with bottle-glass.

When Moon walked the streets,

arguing with angels.

Man, that Purple.

When we drank in graveyards

and the woods behind the armory.

The unmowed fields thick with fireflies.

A summer of conjuration.

Papé Satàn, papé Satàn aleppe

Clusters of black cats and birds,

bullets and Benzedrine

Crows and Catfish

gatekeepers of history

burst from the floor, the attic, the safe.

Clouds of starlings like plague

thorn-bearing robins

turkey buzzards and red-tailed hawks

in the flooded fields, they wheel

indignant smoke of cold fire

72 names and sigils never enough

bats in the streetlights.

The old bones and tools

are plowed to the surface

chipped flints

beads and potsherds.

The swimmers all go into the dark, one by one.

The paths to the hilltops grow over.

The houses of my dying city grow silent.

The thick grass is mown and dark.

The names carved and painted on the stones weather away

These are secrets that are not mine to tell:

Eric Deer shot morphine from dermal packs

with his father, a junkie lawyer, and his wife.

They left him to die on the floor.

Tim Cantrell died alone.

Chuck Broughton died on the toilet

of the SuperAmerica Gas Station

in the flickering light.

Tom King shot poison in his blood in Africa

building cell phone towers

and had his hands amputated

and his friends shot heroin into his stumps

and he died.

Anson Edwards died

and they wrote his name

on the end of the bar, and did lines off it.

Jaybird Ferguson closed the bar

for the last time

played boogie-woogie piano records

for death when he came for him.

Late at night,

while you're sleeping

you will hear my lonesome call

Danny Bailey drank himself to death

with unpainted canvases

and plaster falling to dust.

Matt Stepp died castled in pain.

And I have drank with these dead men

on the river bottoms

in the red light of the burning city

I carry their history in my mouth

They crowd the trench, and speak

while my family waits

in the grey asphodel

the dust thick in their eyes

like white velvet

wing-scale of West Virginia Whites

asbestos falling from a burst pipe

ice and river water.

These my kin, and also:

Great-Uncle Rainy P. Adams

his mules posed in black and white

on his Christmas cards

his children unmentioned.

Nolda, offered up to an accomplice

like a prime pig in trade for silence.

Her dead daughter.

Her granddaughter off to the whorehouses and

stuffed fat full of Warnie's secrets.

Neva left on the steps of a house full of unsleeping dead

her children in the rotten ruin of my father's bed.

My mother offers to her newest man

to sleep in bed with her granddaughters

my sisters children.

So much kindling for the furnace

that cannot be cooled.

Little fish to catch the larger.

Spends a corpse's money on a plastic face.

A face to meet the faces that you meet

the ugly child hides inside the steaming barn

the ghosts crowd behind her

thick as cream in the bucket.

My own inventory of apologies and amends

because I, too, am kin to the bad heart

the slow blood.

Have enacted all my lessons

brightest of students

and only now, unlearn, undo

unmake, unbreak.

Panderers and seducers

Malebolge, burning sand and tortured wood

Habitation of unclean birds

I will keep no secrets here.

Beyond the end of naming

I am sick with secret language,ohio ohio

swollen like a snake-bitten dog

with my parents crimes.

Ye are of your father the devil,

and the lusts of your father ye will do

Better to pray to the iron god.

Better to claim the hangman's pearls.

Like the trees of that final grove

this burning sand.

Break my branch, and words and blood

come burbling out. Come hissing.

Better that.

Harpies and furies nest in my branches.

I the habitation of woe

The tree growing from the burial mound

my roots entangled in the bones

and the unclean earth.

My broken, toothless mouth.

I am unclean, uneducated

poor white trailer trash

child of murderous blood

smeared over all

with the lusts of my father, the devil

so hungry my belly thinks my throat is cut

What then to praise?

Hang a kilt snake in a tree to make it rain

Raise the brazen serpent

Raise up that which is broken,

that which is cracked, and flawed

let light shine through the blue-chipped glass

of a broken pot, iridescent with long burial

let the house burn bright, a holocaust of offering

the piano-keys curling in poisonous smoke

the photographs

the stained and bloody beds

burned down to black iron

the rotten floorboards

the mice

the cattle

the pigs and cars and crane

let them all be transfigured utterly

into something incandescent, something holy

Shall we gather at the river?

Let the rain come and swell the Ohio

like a snake with a mouse in it's stomach

let the glutted mouth of hell sink and sleep in the mud

let the empty city fall into silence

and all her ghosts, and all her ghosts

sleep in the holy dark

Let the embers we have been ignite

the black coal of the world.

Let the streets burn hot below our feet.

Let the barges sink and strew

the coal on the river's bed.

We will sing.

In the burning house of history, we will sing.

In the collapsed mine's darkness visible.

In the dead towns and county-line-bars.

In the dry counties and Sunday service.

Lifting serpents, drinking strychnine, we sing

with broken teeth

with twang.

In my name shall they cast out devils;

they shall speak with new tongues;

They shall take up serpents;

and if they drink any deadly thing,

it shall not hurt them;

they shall lay hands on the sick,

and they shall recover.

Our mouths open in praise

confirming the word with signs following

in horror, in awe

we will sing of murder

and bodies and the riverside

we will sing of the unbroken circle

of the ice of time

and the graves of our parents

we will sing, poor, unshod

sick with our lungs black

riddled with cancer

from yellow smoke and dirty water

with the poisoned, holler-fill earth below our feet

I drew my saber through her

it was a bloody knife

I threw her in

the river

it was an awful sight

we will sing over the graves of our children

those toy strewn, flowered accusations thrown

in the blind face of god

we will sing praises in spite, in survival

in anger and through broken teeth

in sorrow and lamentation

will the circle be unbroken?

by the river we lay down and wept

and hanging our harps in the trees, we sing.

Sing happy are those who pass through the fire

happy are those who are dashed against the rocks

happy

sing

The Thunders of Judgment and Wrath are numbered

and are harbored in the North in the likeness of an oak,

whose branches are Twenty-Two Nests of Lamentation and

Weeping laid up for the Earth, which burn night and day:

and vomit out the heads of scorpions

and live sulphur myngled with poyson.

Sing of beasts before the throne

and the muddy river, of mountain-top removal.

Sing woe, woe, woe, to the earth

for her iniquity is, was and shall be great.

Sing throats of teeth, of Benzedrine and bullets

of blood and beds, coal-ash and arsenic but sing

tell everything. There is nothing secret

that does not rot.

There is no silence

in which we are not complicit.

Which side are you on?

Sing blessing and malediction.

Sing corn from the ground.

Sing rain and fish and company scrip.

Sing plenty, sing famine, sing fire and flood.

Sing trees growing through the logging roads

through roofless houses and rusted plows

and lost sedans on the river bottoms

and houses burning

and the fields sown with salt.

Sing the bodies from the earth.

Sing themway up in the middle of the air.

Sing the saints, those used-car lot balloons.

Sing the elect, the silence in heaven.

Sing the end of all things, but sing.

Are you washed in the blood?

Sing.

This I give you, my children, and my children's children.

My city of dead, my butchers and my union-men.

Sing with the dirt in your mouth.

The hot song clotting your teeth

through your bitten tongue.

Which side are you on?

Not the blood, not the knife

not the door we enter in

hellmouth or heaven

not the river, not the ice

not eyes in the underbelly of the woods

not bloodbait or moonshine

no gun or safe or paper money

not ghost-thick road

not dogwood ridge

not furnace

but the song that does not end.

The miracle of your own survival

to live, and flower

chicory in the corn

spurge in the pavement

you steel-mill ivy, you tree on the ridge

you explosion of birds

in this charnal house

in this bone-fire

in this mouth

this blood

this flood

this dark

this river.

Sing.

Jacob Rakovan

Acknowledgments

Excerpts from this long-form poem have appeared in The Chicago Review

and Drunk in a Midnight Choir

“But when I had besought the tribes of the dead

with vows and prayers,

I took the sheep and cut their throats over the trench,

and the dark blood flowed forth, and lo,

the spirits of the dead that be departed

gathered them from out of Erebus.“

Odyssey Book XI

Sing.

Outside the girdled ring of firelight,

the city's floodwalls,

the shakily chalked circle and

the thousand names of god.

Call the dark up to speak.

Hang the deer from the rusted swingset

Let the throat open.

Let blood be a song.

Be a river.

Let the black song splash against

the galvanized washtub.

Pour blood in the ditch

and sing a litany of names.

Put questions to the woods,

to the mine

to the ridges

to the grave

to the cold stars of our forgotten home.

Let gun and stolen hoard speak.

Let the door of the house hang open.

Let the earth disgorge what it holds

Let the catfish-barbed mouth of hell gape.

Sing.

Warnie Risener, hillbilly conman,

entrusted with keeping of store and post office

has engineered a plan

with Harland Roark.

They have stolen a safe filled with banknotes

the mortgage payments

the back taxes

the book of credit accounts

and the Sears & Roebuck checks.

Warnie has run, been caught, gone to prison.

The safe and money have not been recovered.

Warnie has done his time in silence,

grimly waiting within the walls for the jailhouse key.

Warnie has kept his mouth shut,

tight as a gunsafe lock

knowing how to keep a secret

and the metal doors swing wide.

Harland Roark, an educated man, a schoolteacher

with two daughters

and a criminal inclination

is thankful for this.

Warnie's Colt Police Positive .38 Special

has been used to put a bullet

in the workings of another man

to burst all his intricate plumbing

and let his death come leaking out

in a mine-dark stream

the unsung steaming song

that clots in the washtub

that the ditch-clay drinks.